by Milton Dawes (1994)

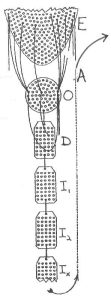

To view a large version of the Structural Differential, click here.

- what is going on beyond our immediate and direct observations (the “sub atomic level” within the parabola);

- our direct observations (the “object level” represented by the circle below the parabola);

- and what we might ‘think’, ‘feel’, believe, assume, imagine, theorize, speculate, etc., regarding what we observe to be going on (the tags below the circle).

The following provides an example of an experiment exercise you can do to improve your ability to differentiate. Developing these differentiating skills may enable us to:

- minimize distress in our lives

- better grasp the many aspects of diverse situations

- improve our communication skills

- become better problem solvers

- better manage our many varied social interactions and relationships

- avoid and resolve many conflicts

- more effectively manage ourselves and the situations we find ourselves in

How can we achieve all this by focusing on differences? By increasing our evaluating flexibility, refining our sensitivity and awareness, and expanding our behavioral options.And you don’t have to just take my words for it – you can try your own experiment exercise and judge for yourself. Here is an experiment exercise you can do anywhere, anytime. Dedicate at least 10 minutes each day for this, until you find that it begins to become a habit.

Make your own little sketch of the structural differential, similar to those shown on the left. Carry it around with you. When you find the time (or more appropriately, when you make the time), look at someone, or some thing, or some situation you are in. Say to yourself, while looking at the parabola/event level (“E” in this diagram) at the top of your sketch: “I don’t know, I can’t see, hear, etc., what’s going on at the sub microscopic levels, of this person, thing, or situation. In fact, I am not aware of most of what’s going on around me. And, I am never aware of ‘all’ that’s going on anywhere.”

Make your own little sketch of the structural differential, similar to those shown on the left. Carry it around with you. When you find the time (or more appropriately, when you make the time), look at someone, or some thing, or some situation you are in. Say to yourself, while looking at the parabola/event level (“E” in this diagram) at the top of your sketch: “I don’t know, I can’t see, hear, etc., what’s going on at the sub microscopic levels, of this person, thing, or situation. In fact, I am not aware of most of what’s going on around me. And, I am never aware of ‘all’ that’s going on anywhere.”

How does this help you become more discriminating? If we accept that we don’t know ‘all’ that’s going on around us, we’re less likely to be close-minded about our ideas, opinions, decisions, etc. We are more likely to listen to what others have to say and more tolerant of the diversity of interpretations, understandings, beliefs, and behaviors (within limits of course) of others. We become less confrontational, minimizing the potential of conflicts and disagreements. With an awareness that we don’t know ‘all’, we are less blocked, more open-minded, and more motivated to try other approaches to formulating and resolving problems. We become more creative individuals. If we accept that we don’t know ‘all’, we are more likely to develop a theoretical, experimental, and less absolutistic approach to what we believe, what we understand or know, and what we do. We adopt a continuous learning approach to living when we are aware that there is more information available to us than what we presently have.

Next, look at the person, or thing, or situation, while glancing at the object level (“O”) of your sketch. Let your eyes wander. Survey the scene. Look at colors, marks, outlines. shapes, gestures, movements, placements, and listen to the surrounding sounds. Feel the textures of different things around you. This level represents our ‘sensing’ of things. When you catch yourself saying or thinking something, say to yourself quietly (hear yourself saying this), “Silence on the sensing level. Words can sometimes blur my vision, dull my senses. Things are not what I say, think or believe they are. There are others who are not sensing what I am sensing.”

Next, look at the person, or thing, or situation, while glancing at the object level (“O”) of your sketch. Let your eyes wander. Survey the scene. Look at colors, marks, outlines. shapes, gestures, movements, placements, and listen to the surrounding sounds. Feel the textures of different things around you. This level represents our ‘sensing’ of things. When you catch yourself saying or thinking something, say to yourself quietly (hear yourself saying this), “Silence on the sensing level. Words can sometimes blur my vision, dull my senses. Things are not what I say, think or believe they are. There are others who are not sensing what I am sensing.”

At first, you are likely to find talking this way to yourself a very difficult thing to do. You might feel a bit silly at the beginning. But with continued practice, you might find that it gets easier and easier, until it takes no effort. Our nervous systems develop habits with great ease. After some practice you will be able to look, listen, feel, etc., with a heightened sense of self-awareness, without actually talking out loud to yourself.

Then move to the descriptive label level (“D”). Look at a person or object and give it a name, make it up – call it “[label]”. Now describe what you’ve labeled. Be careful in your describing – you might find that some assumptions, opinions and inferences creep in under the disguise of description. Say only what you see, right there before you. Then say quietly to yourself, “What I call [label], how I describe [label], what I might think, believe, or feel about [label], is not the person or thing I’ve labeled. I cannot see, or hear, or sense, ‘all’ that’s before me. My words, my labels, are not the same as the person or thing I’m talking about. I am here, the person or thing is over there. What I say about [label] could not possibly be [label].”

There is a vast difference between words and what they refer to. The word is not the thing process it represents, any more than a map (or words, beliefs, understandings, theories, opinions, expectations, hopes, wishes, etc.) is not the territory it maps. Others may describe (or “map”) the situation quite differently than you. They are not ‘seeing’ exactly what you are ‘seeing’, from your unique perspective.

Now, look again at the person or thing you’ve labeled. Glance at the inferential level (“I1“) on your sketch of the structural differential. Imagine something about [label]. Ask yourself, “How do I know that what I ‘think’ or say, or believe about [label] is so?” Then say to yourself, “I am imagining things. I am assuming things. Others might be making different assumptions, imagining different possibilities. I might not be entirely wrong. But at this moment, I don’t know how accurate my map of [label] is. If I had more information I could critically evaluate about [label], I could make a more accurate map. How might I get more information about [label]? If I have to make decisions with the information I now have, I must prepare myself for the possibility of a ‘mid course correction’ if new information becomes available.”

Now, look again at the person or thing you’ve labeled. Glance at the inferential level (“I1“) on your sketch of the structural differential. Imagine something about [label]. Ask yourself, “How do I know that what I ‘think’ or say, or believe about [label] is so?” Then say to yourself, “I am imagining things. I am assuming things. Others might be making different assumptions, imagining different possibilities. I might not be entirely wrong. But at this moment, I don’t know how accurate my map of [label] is. If I had more information I could critically evaluate about [label], I could make a more accurate map. How might I get more information about [label]? If I have to make decisions with the information I now have, I must prepare myself for the possibility of a ‘mid course correction’ if new information becomes available.”

Now I am not suggesting that you use the precise words I used above – you can of course make up your own. Remember that the purpose of this rather explicit experiment exercise is to help you improve upon the differentiating skills you already possess and use to some degree, in some situations.

The next level of your sketch represents the next level of inferences we call generalizations (“I2“). Look around you, reminding yourself that you are not seeing, that you cannot see, all that’s there to be seen. Now make up some generalizations, such as, if you see a person wearing sneakers, “People who wear sneakers are athletic.” Or if you see person wearing a ring on a particular finger, “People who wear a ring on that finger are married.” Say to yourself, “Other people like me are standing in a different place time and making their own generalizations. They don’t ‘see’ exactly what I see’ or ‘all’ that I ‘see’ and are likely to make different opinions, different expectations, and different evaluations.”

Might this simple awareness potentially reduce the number and degree of our personal misunderstandings and conflicts?

The bottom tag – the one that appears to be ‘broken’(“Ix“) – serves to remind us that there is no end to our ability to make such distinctions. We can make assumptions, and generalizations, and conclusions, without limits. We make assumptions about our assumptions, we make opinions about our opinions and about others’ opinions; we make generalizations about our generalizations, theories about our theories, philosophies about our philosophies, ad infinitum. We can, and do indulge ourselves with words and more words, about our words often taking ourselves further and further away from what we can observe or sense going on in the rest of our surroundings.

The bottom tag – the one that appears to be ‘broken’(“Ix“) – serves to remind us that there is no end to our ability to make such distinctions. We can make assumptions, and generalizations, and conclusions, without limits. We make assumptions about our assumptions, we make opinions about our opinions and about others’ opinions; we make generalizations about our generalizations, theories about our theories, philosophies about our philosophies, ad infinitum. We can, and do indulge ourselves with words and more words, about our words often taking ourselves further and further away from what we can observe or sense going on in the rest of our surroundings.

The broken line and arrow pointing us back to the next parabola (symbolizing our next sense-experience-at-a-time) remind us to not to get lost in our human jungle of words. We can minimize potential confusions by returning as often as possible to what we can directly sense and observe, remembering that what we ‘observe’ is itself an abstraction, or a selection, that our nervous system has created from whatever is going on around us at sub microscopic levels. If we build our relationships, institutions, and societies mainly on words, definitions, and unquestioned beliefs – rather than on critical evaluations of our shared observations – we risk perpetuating conflicts and disagreements, rather than solving them.

A map is not the territory it maps. The ‘territory’ – the world we live in – does not operate as a grammatical system. We can say quite properly, in the grammatical sense, that “the cow jumps over the moon,” “this car or this airline, is ‘safe’,” “we will provide jobs for everyone,” “we will wage war on drugs and crime.” And we can believe quite strongly in our words. However, if we put more faith in our words and ‘maps’ than in what we see, hear, feel, smell, touch, etc., we will constantly be at odds with what’s going on in and around us. The universe does not care about our words.

This is not to say that we don’t need, or that we can do without, fantasy, imagination, theories, hopes, opinions, and so on. What I want to emphasize is that we need to question ourselves regarding … to which do we assign the higher priority, give greater value, consider more significant? Our words and our maps … or the actual person, thing or situation?

We ought to remember – for our own health, sanity, and relationships – that the ‘things’ in our lives existed before we had our own words to label them. We do ourselves and others a favor when we attempt to better understand how things work, how they are structured, how they relate to other things, etc., rather than focusing on the labels we assign to them.

The more skilled we become at distinguishing between our verbal word-labels and our non-verbal sense-experiences, the more we expand our awareness, improve our thinking-feeling evaluating skills, and broaden our understanding of things. I invite you to practice this experiment-exercise using your own sketch of the structural differential. See if it makes a difference in your life. As a fellow time binder, I can say that it has made a big difference in my life, as I continue to modify my own thinking, feeling, analyzing, judging, understanding, and deciding. Etc.

An extremely worthwhile adjunct to the sine qua non of making your own structural differential. A key ring would also be a great means of reminder in going through the steps, feeling the different levels etc.